Setting the Air on Fire

Right before the first nuclear bomb test in New Mexico, Enrico Fermi joked, “Let’s make a bet whether the atmosphere will be set on fire.”

His colleague Edward Teller had brought this up as a real risk in 1942, but by 1945, almost all the scientists were convinced it couldn’t happen.

James B. Conant, a former chemistry professor and Harvard president, who was there in his role as the Chairman of the Office of Scientific Research and Development, which supervised the Trinity Project, wasn’t so sure. But he didn’t do anything to stop the test.

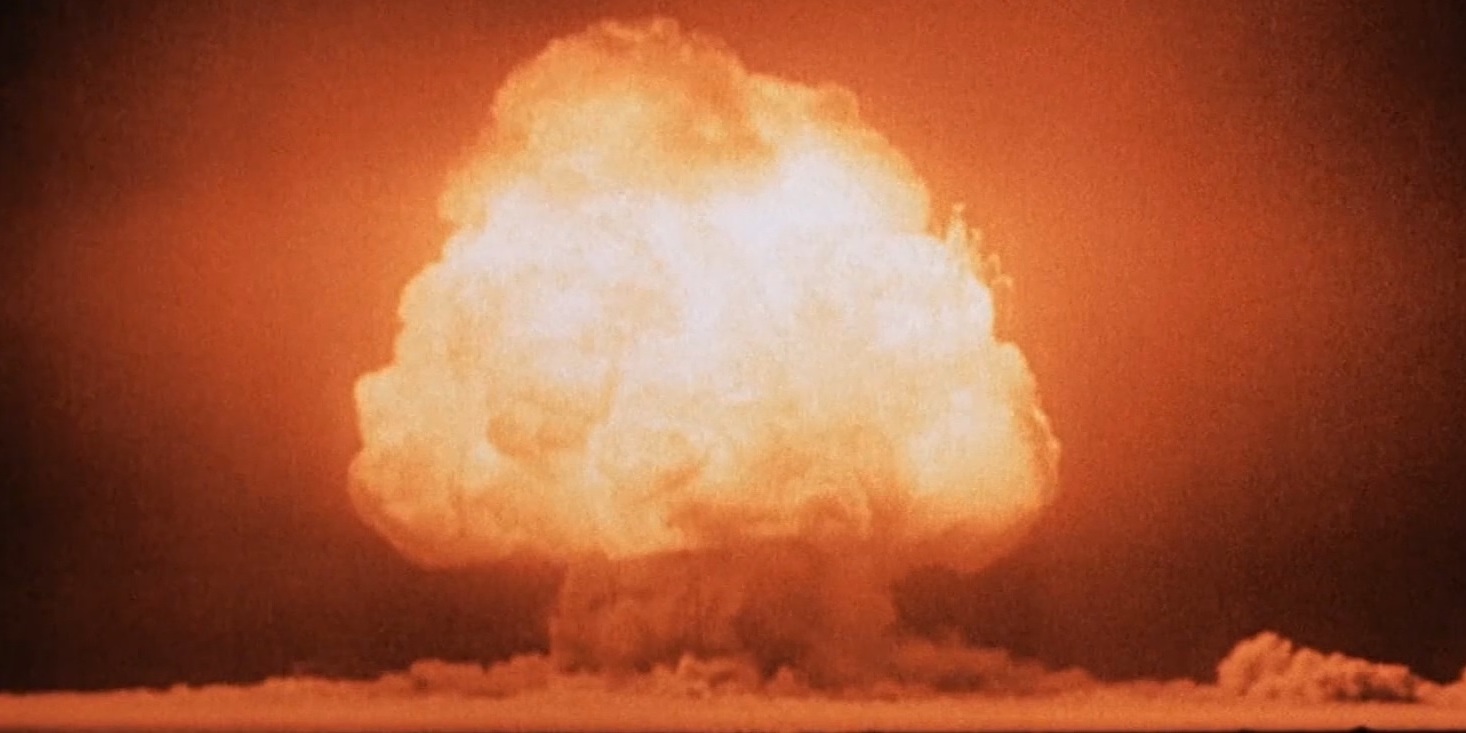

During the Trinity test, according to Conant’s journals, the “enormity of the light and its length” made him believe “the thermal nuclear transformation of the atmosphere, once discussed as a possibility and only jokingly referred to a few minutes earlier, had actually occurred.”

Here’s what it looked like in colour:

And in motion, but in black and white:

Imagine believing that there was a real risk that an experiment you were responsible for would set the air on fire and end life on earth, and signing off on it anyway. And then imagine believing when the test took place that it was actually happening.

My friend Christy wondered if that experience changed his outlook on life. The answer is no, he actually went on to do a great deal of evil.

First, he was part of the committee that advised Truman to drop atomic bombs without warning on Japanese cities.

Worried about public perception of the use of the atomic bombs, he initiated and edited an an essay co-written by Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson that was published in Harper’s in 1947, which claimed the bombs prevented a million US casualties.

During the Red Scare, Conant called in 1948 for a ban on hiring communist teachers and in 1952 for the firing of academics who pled the Fifth while being questioned by the House Un-American Activities Committee.

As United States High Commissioner for Germany starting in 1953, he released Nazi war criminals such as Martin Sandberger after serving a small percentage of their sentences and supported the attitude of the West German government at the time of forgiveness toward Nazis.

And finally, after returning from Germany in 1957, he dedicated himself to educational reform. He supported segregated schools until by 1964 it was no longer politically savvy to do so, at which point he said he had been wrong to do so.

To be sure, Conant probably had the attitudes that led him to his bad behaviour before his experience at Los Alamos, and it was only after that he was in a position to take action on them. For instance, some research indicates he already had Nazi sympathies in the 1930s.

But it is still noteworthy that having an existentially traumatic experience so unimaginable that he was the only person in history to have ever undergone it, Conant didn’t come out of it with any further humanist leanings, at the very least.

And to close this all off, what did Conant get from all his bad behaviour?

Fifty honorary doctorates and a bunch of other decorations. I was unable to determine exactly why he was awarded with each, but I’ve included my best guesses:

- Conant was awarded the US Civilian Medal for Merit and became a Commander of the Order of the British Empire after WWII. Both honours were for civilians who distinguished themselves in the war effort, so they were likely for his part in developing the atomic bomb.

- He received the Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany after finishing his term as High Commissioner. He was aligned with the government at the time in his lenience toward Nazis, so he probably received that for the total of his work in his role there, Nazi-related or not.

- Time put him on the cover after the publication of his bestselling Conant Report (formally known as The American High School Today: A First Report to Interest Citizens) on education reform.

- And John F. Kennedy decided to award him the Presidential Medal, but was assassinated before the ceremony, and Conant received it from Harry S. Truman. Presumably it was for the sum of his service to the United States.

And now, to end with some music again, I think we’ve got to go with the obvious choice, The Prodigy with their 1996 banger, “Firestarter.”

Subscribe to The Golden Age of Apocalypse

Get the latest posts delivered right to your inbox